Archive of the month: Memories of China 1900/1901

Every month, the German Maritime Museum (DSM) / Leibniz Institute of Maritime History presents a special treasure from the archive in the “Archival of the Month” series. In November, Dr. Alexander Reis recalls the Boxer War in China.

In the spring and summer of 1900, an uprising against European colonial involvement in China emerged from the so-called Boxer movement. The uprising was fed by the religion and culture of northern China and was based on a variety of interwoven causes. It found support above all among the rural population and thus spread far and wide.

Kaiser Wilhelm II was the supreme commander of the imperial army and navy. He urged a large contingent of German troops to quickly participate actively in the suppression of the uprising and ordered the mobilization of the navy. On July 2, the Kaiser then ordered an East Asia Corps to be sent to China. As early as the 1890s, Wilhelm described China as the “yellow peril”, a direct threat to Europe. This view of a threat to Germany was also expressed in his address to the shipyard workers of Bremerhaven on August 3, 1900, when he spoke of a danger to the fatherland.

German participation in the war against the Boxers led to the first comprehensive shipment of German soldiers totaling over 22,000 men with equipment and around 6,000 horses. This transfer of men, animals and material sheds light on the relationship between the German shipping companies Norddeutscher Lloyd and HAPAG and the military, as well as aspects of the social, political and cultural conditions in the German Reich.

With the help of steamships, which were converted by NDL and HAPAG for this purpose, the transport was put together in a short time in the summer of 1900. The military was able to use ships from the Reichspostdampferdienst, which was subsidized by the German Reich. In the event of mobilization, the ships could be used by the navy for a fee. Bremerhaven was the main port for transportation: from July 27 to September 7, eight HAPAG and ten NDL steamers sailed from there.

Wilhelm II interrupted his Nordland voyage, which usually took place in July, and came to Bremerhaven on his yacht Hohenzollern to personally inspect the ship's equipment and disembarkation. Although the harbor area where the embarkation took place was cordoned off except for members of the military, thousands of people gathered when the steamers departed. Because of the large number of visitors, the beverage manufacturers set up drinking halls, dispensing points and beer and seltzer stands near the embarkation point on troop transport days.

The steamships and facilities of North German Lloyd formed the backdrop and stage for Wilhelm II's speech to the departing crews at noon on July 27. The speech, which later became known as the Hun Speech, together with the port where maritime power, militarism and nationalism were staged, helped to reinforce the Chinese image of the enemy at the time. The speech was readily received by the soldiers, such as the slogan from it “Pardon will not be given!”

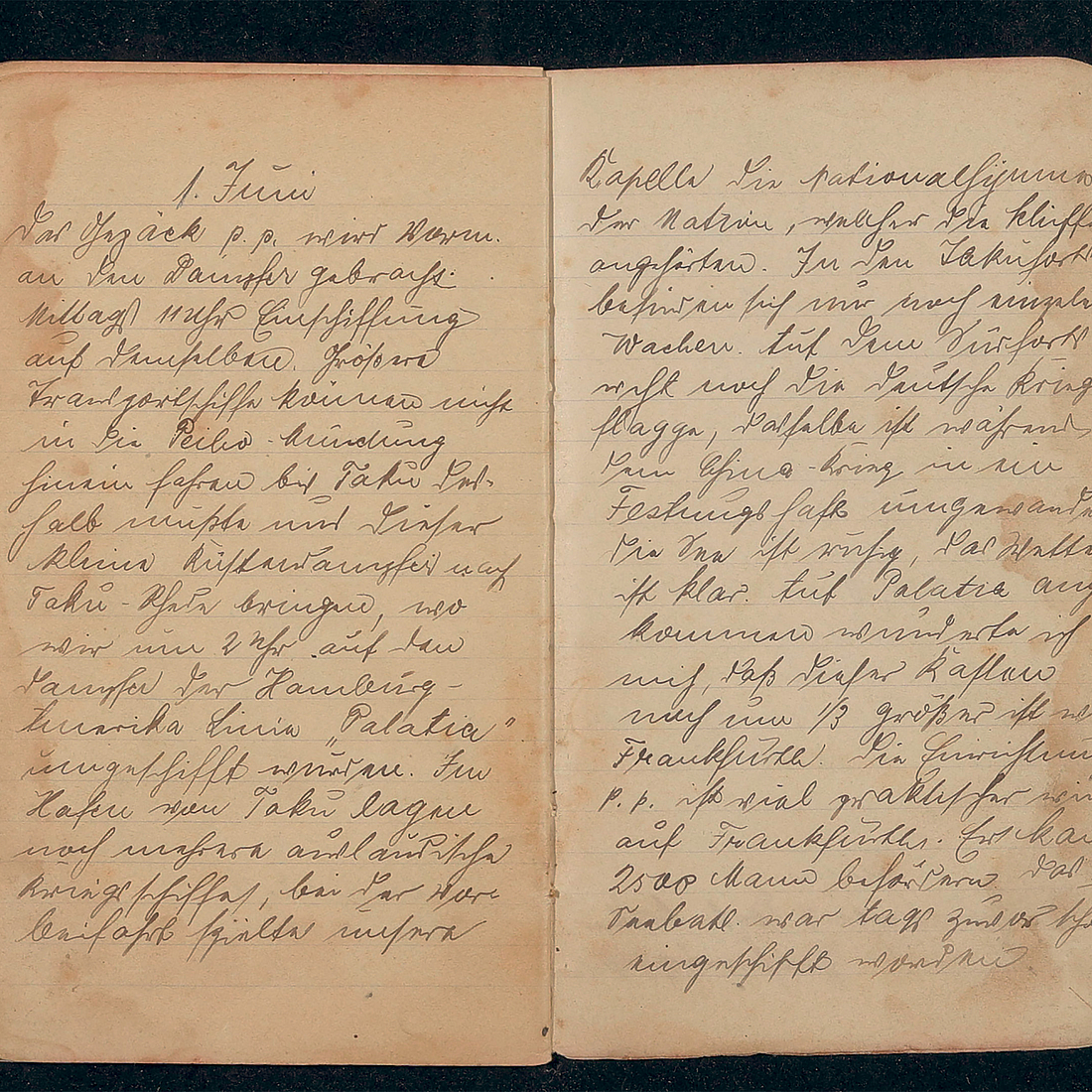

There was no special preparation for the upcoming deployment in China for the soldiers and previous prejudices about the Chinese were not questioned during the crossing. This pronounced racism then came to light when the Germans were deployed in China. There are numerous private documents about the conditions of the crossing in the form of war diaries. The DSM archive also contains a fragment of a diary of a member of the second naval battalion who is unfortunately no longer known by name (Fig. 1). In all the diaries of the German soldiers involved, the description of the extreme temperatures on the ships during the crossing of the Red Sea takes up a certain amount of space.

An attempt was made to incorporate barracks life into the troopships with all its inherent regularities, to create “floating Prussian barracks” so to speak: “Thus our ship became our home and barracks for a long time,” wrote Gustav Paul, sergeant on board the PALATIA on departure from Bremerhaven, for example. The commander of the East Asian Expeditionary Corps, Emil von Lessel, emphasized the ship as a self-contained place on the endless sea when he wrote on board the RHEIN on 7 August 1900: “You sail in a world of your own, and nobody suspects what is going on outside”.

Due to the heat during the voyage through the Red Sea, NDL and HAPAG organized the horse transports from Australia and America. The rapid assembly of the transports led to difficulties, not only because the equipment and war materials were often unsuitable for use in China, but also because of the unfavorable loading of the ships in Bremerhaven during disembarkation in Dagu, China.

However, the German soldiers sent did not arrive until after Beijing had been conquered by a European force. The result was an asymmetrical war that consisted only of so-called punitive expeditions and no longer distinguished between insurgents and uninvolved parties.

By the time of the Peace Protocol on September 7, 1901, hundreds of Chinese had been killed with heavy German involvement. In total, there were only 65 German casualties. When the troop transports returned from China from May 1901 (Fig. 2), the sick and wounded were cared for in Bremerhaven in 16 specially erected barracks on the east side of the Kaiserhafen. Warriors' associations in Bremerhaven and the “Vaterländische Frauen-Verein, Bremerhaven” decided to erect a memorial “to the comrades of the East Asian Expeditionary Corps who died here” at the cemetery in the Wulsdorf district of Bremerhaven, which was dedicated in 1903.

Painting of the steamer STUTTGART.

Photo: DSM / Archive

Entry from June 1, 1901 about the disembarkation from China on the PALATIA in a diary of a member of the second sea battalion. D

Photo: DSM / Archive