Provenance research at the German Maritime Museum: An old engine and its history in the NS era

In 1911 Nathan Forchheimer, owner of a fulling and knitting factory in Regensburg, ordered a single-cylinder four-stroke engine from MAN. The engine has been part of the collection of the German Maritime Museum / Leibniz Institute for Maritime History since 1976, but for a long time its origin was unclear. Now, in the course of its provenance research, the museum has discovered that the engine was unlawfully confiscated from the former company owners during the Nazi era. The heirs were located through an elaborate process and their legal property is now being restituted. They will conclude a permanent loan agreement with the German Maritime Museum so that the engine can still be exhibited.

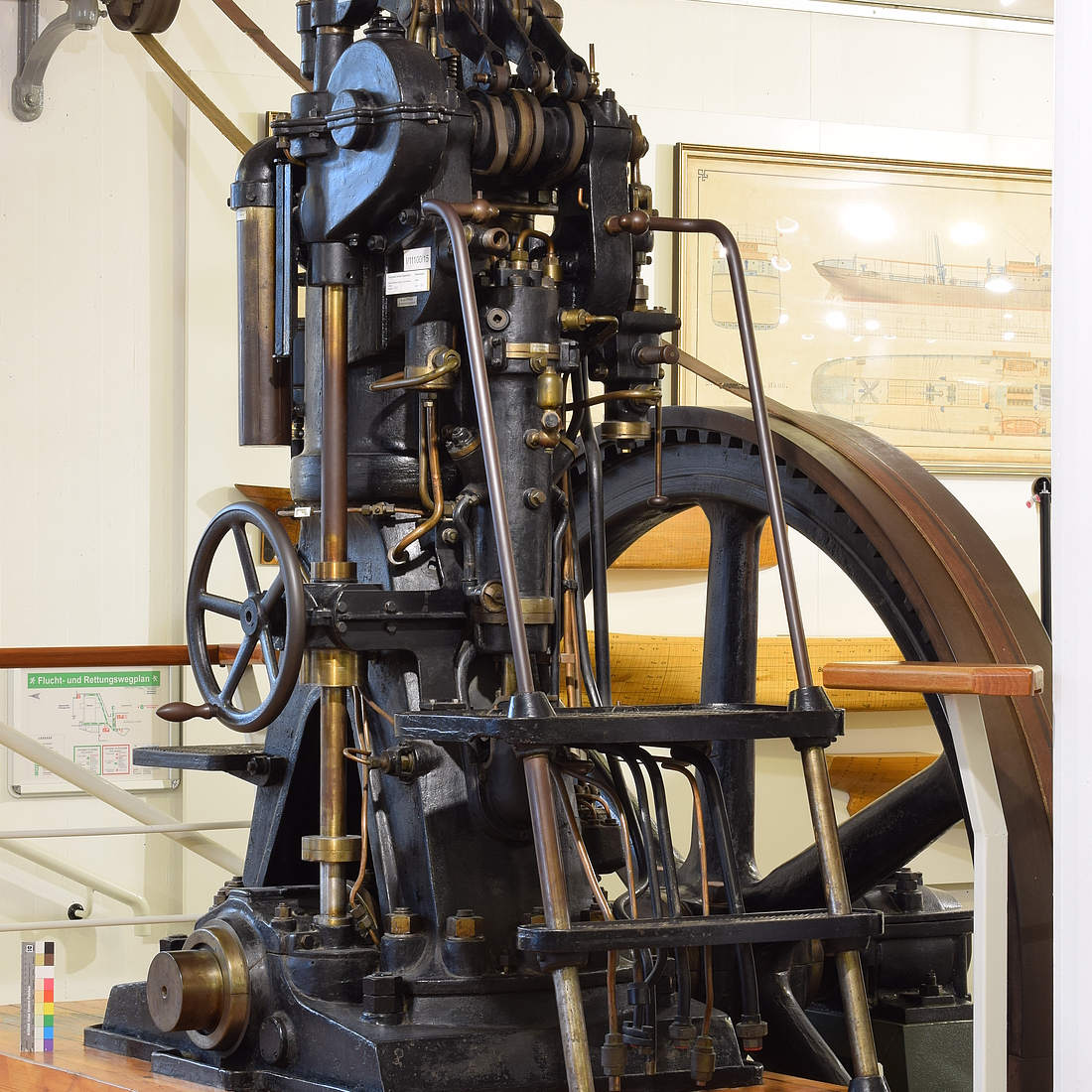

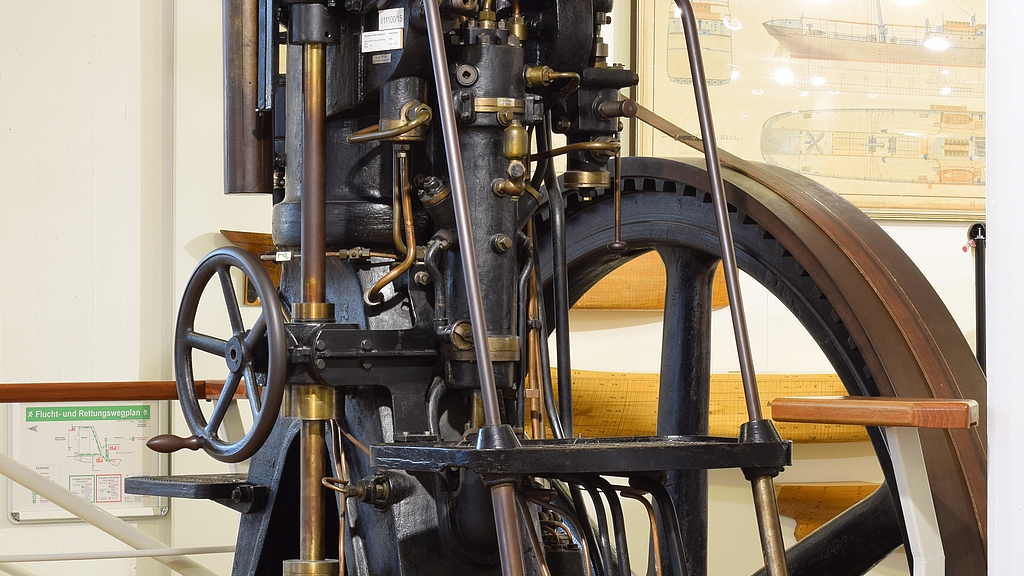

How did such an engine get into the German Maritime Museum? According to a newspaper article in in 1976, it came into the possession of the museum after having previously served as an emergency power generator on an estate. Before it was used as a museum object, MAN overhauled it once again in order to exhibit it in a fully functional condition as an example of earlier forms of drive. The engine will also find a fixed place in the new permanent exhibition that the German Maritime Museum is currently designing. Further information on the engine can be found in the Lost Art Database

.

The starting point for the discovery of the unlawful possession was the question of what role the engine has played in shipping and the knowledge that it came from Regensburg and was owned by Jewish people there. Dr. Kathrin Kleibl, provenance researcher at the German Maritime Museum, thereupon went looking for further details and found out that the Forchheimer family, pushed by the Nazi regime, was forced to sell the business to the company Rathgeber at far below value and emigrated to the USA afterwards.

All equipment of the predecessor company went to Rathgeber and remained in the company, such as employees, machines or materials. This also applied to the engine examined by the museum. Kleibl’s search for the descendants was made more difficult by the fact that they changed their names when they entered the USA.

Forchheimer's descendants, who have lived in the United States for several generations now around Pennsylvania, Illinois and Florida, would like to see the engine preserved for the museum. They have agreed to give the engine to the German Maritime Museum on a permanent loan on condition that a note accompanies it on its history. A plaque with a note on the original owners of the engine and a reappraisal of its history in the course of the family's persecution and emigration will be placed next to it in the future.

The Forchheimers have an extraordinary emigration history: Rosalie Forchheimer, widow of the company founder Nathan Forchheimer, only left Germany shortly before the beginning of the war in 1939. While the other family members had already emigrated to the U.S. in 1938, she continued to maintain the house belonging to her property, which bordered the sold company premises.

She took in many people persecuted as Jews there at low rent until she was forced to sell the house under the political pressure of the Rathgeber Company. The reason given for this was that the "Aryan" employees of the company did not tolerate the Jewish tenants during their break.

Kleibl's research also revealed that the family's company building of that time still exists. Today it houses a boarding school. The school director was inspired by the German Maritime Museum's research to initiate a history project with his students in which they work through the biography of the house.

The way to locate possible descendants of an object to be restituted is always individual and is often connected with detective work. In this case, it was possible to reconstruct a family tree by using several genealogical databases. Obituaries of the deceased son of Karl Forchheimer in turn provided names of his children. In the end, Kleibl came across an heiress working as a teacher, who immediately contacted other family members.

The research took place within the framework of a three-year provenance research project at the German Maritime Museum, which is financed by the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste in Magdeburg (German Lost Art Foundation). In this context, the German Maritime Museum systematically examines its holdings for cultural property unlawfully confiscated during the Nazi era.

The soon to be restituted engine, which will be available to German Maritime Museum on permanent loan.

Photo: German Maritime Museum